In 2003, President Bush declared that the U.S was going to invade Iraq due to a growing suspicion that Saddam Hussein was developing weapons of mass destruction. The debate as to whether or not Iraq had WMDs was highly controversial, as it incited a 15-month long investigation organized by the CIA and the Pentagon. On September 30, 2004, the highly-publicized Duelfer Report was released, which concluded that Iraq did not in fact possess any WMDs nor any significant means for developing them.

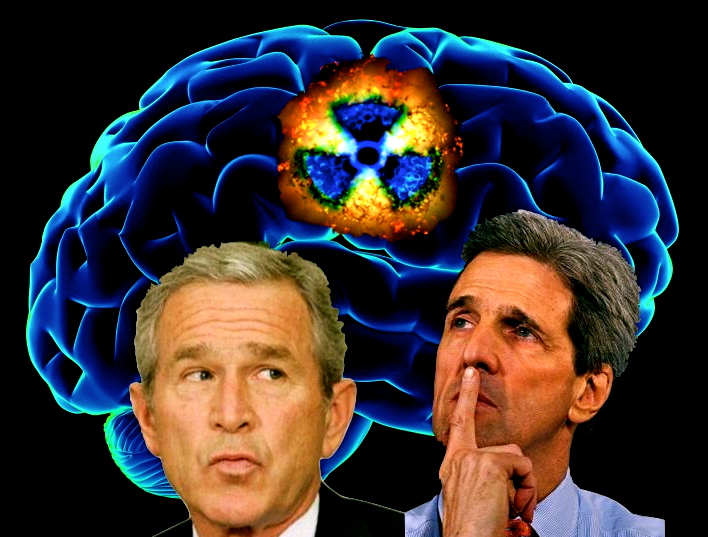

Despite these findings however, a survey conducted by the Project on International Policy Alternatives (PIPA) a month following the Duelfer Report release, reported that 47% (!) of Bush supporters still believed that Iraq possessed WMDs, and 25% believed Hussein had programs in place for developing them. Conversely, according to that same PIPA survey, supporters of John Kerry, the Democratic presidential candidate at the time, did not believe Iraq had WMDs nor the programs to develop them. So why, despite the same evidence being presented to both groups, was the distinction between beliefs so strongly correlated with party affiliation. Well, a bit of psychology can answer that.

The Bush supporters who participated in this survey were most likely exhibiting what is known as belief persistence (or belief perseverance), the tendency to identify with old, familiar beliefs even when they have been widely disproven, and no longer accepted as fact. Despite overwhelming evidence, those who demonstrate belief persistence, or “my side bias”, continue to entertain their original beliefs simply because it is easier to keep a current mentality than to conform to a new, unfamiliar side of an issue. In this case, the Bush supporters initially identified with the President’s beliefs that Iraq possessed WMDs, and despite the evidence discrediting this notion, they were unable to assimilate the reality into their political construct. This phenomena is a mechanism of mental resistance; it is likely that when presented with the information in the Duelfer Report, the Bush supporters who had been surveyed, engaged in cognitive dissonance.

Cognitive dissonance is a mental state that arises from conflicting beliefs which causes a sense of discomfort to a degree which leads to a change in one of the beliefs to restore consonance, or balance, between the two ideas. This balance is typically achieved by modifying the new, incompatible belief, or ignoring it all together in order to reinforce the original belief. In this case, the Bush supporters did not want to accept that there were no WMDs in Iraq because that would suggest the President they had put their faith in, had been wrong about such a critical issue of national security, and that might lead one to conclude he was an unfit President, that they had made the wrong decision in voting, etc. So you can see how distressing this thought process might be to a Bush supporter; it seems it is much easier to simply disregard the evidence and reinforce one’s own personal faith in the President.

The main problem that collective belief persistence poses in the realm of politics, is that it undermines rationality and impedes the ability to make informed decisions, particularly when voting. The flat-out refusal to accept evidence that refutes one’s own beliefs causes voters to ignorantly follow their disconfirmed beliefs (also referred to as “unwavering faith”), and by extension, the politicians who represent them. Granted, this is the same psychological mechanism being exercised by Creationists with their young earth belief, but that’s another issue for another time.

The good news is, there is a way to combat belief persistence and selective attention in general, that is only accepting information that reconsolidates preconceived assumptions while ignoring any contradicting ideas. The solution requires a conscious effort to view life through an objective lens, to employ critical thinking when presented with new information, and being generally skeptical about opinions from others without hastily accepting it as the undeniable truth. This requires an open mind and a habit of examining a situation from all perspectives in order to make a well-informed decision on where you stand on an issue.

Its all about emotion versus logical reasoning. Fear of the unknown versus understanding the unknown.

For example why did the radio broadcast of war of the worlds lead to so many Americans believing it?

Posted by Addison Jones (@upukcab) | November 27, 2012, 3:17 pmWhat’s strange to me, is that it seems logical that people would have a stronger tendency to identify with a belief that holds a more positive outcome for them than it’s alternative, but in the example you mentioned, that doesn’t seem to be the case. Media-inspired hysteria is a powerful force..

Posted by Defining My Ethos | November 27, 2012, 3:32 pmI’ve actually heard people to this day say they still believe Iraq has WMDs.

Posted by Mark Duwe | November 28, 2012, 12:33 am